Study No. 3

Do certain personality traits provide a mating market competitive advantage?

Sex, offspring & the big 5

Abstract

This study uses the BIG 5 personality traits to quantitatively explore correlates of sexual frequency and reproductive success of a large sample (NMale = 2998; NFemale = 1480) of heterosexuals advertised to on an Australian dating website. Consistent with previous research we find that for both sexes, extraversion has a positive linear relationship with sexual frequency. The same is also observable for males that are more conscientious, more emotionally stable, and less agreeable; indicating that for men, a greater number of personality factors matter in explaining the variation in sexual activity. Higher extraversion or lower openness in males correlates with more offspring. Conversely, only more agreeable females have more offspring. Our non-parametric thin-plate spline analysis suggests certain combinations of the traits extraversion & agreeableness, extraversion & conscientiousness, and agreeableness & conscientiousness provide select males a mating market competitive advantage in relation to sexual frequency, compared to other males. Our findings suggest that greater variance in male traits and their particular combinations thereof may provide a fitness comparative advantage for males, but not necessarily for females.

Read the full study in Personality and Individual Differences.

Study No. 1

Man, Woman, “Other”:

Factors Associated with Nonbinary Gender Identification

Abstract

Using a unique dataset of 7479 respondents to the online Australian Sex Survey (July–September 2016), we explored factors relevant for individuals who self-identify as one of the many possible nonbinary gender options (i.e., not man or woman). Our results identified significant sex differences in such factors; in particular, a positive association between female height, higher educational levels, and greater same-sex attraction (female-female) versus a negative effect of lower income levels and more offspring. With respect to sex similarities, older males and females, heterosexuals, those with lower educational levels, and those living outside capital cities were all more likely to identify as the historically dichotomous gender options. These factors associated with nonbinary gender identification were also more multifaceted for females than for males, although our interaction terms demonstrated that younger females (relative to younger males) and nonheterosexuals (relative to heterosexuals) were more likely to identify as nonbinary. These effects were reversed, however, in the older cohort. Because gender can have such significant lifetime impacts for both the individual and society as a whole, our findings strongly suggest the need for further research into factors that impact gender diversity.

Read the full results of his study in Archives of Sexual Behaviour.

Appendix

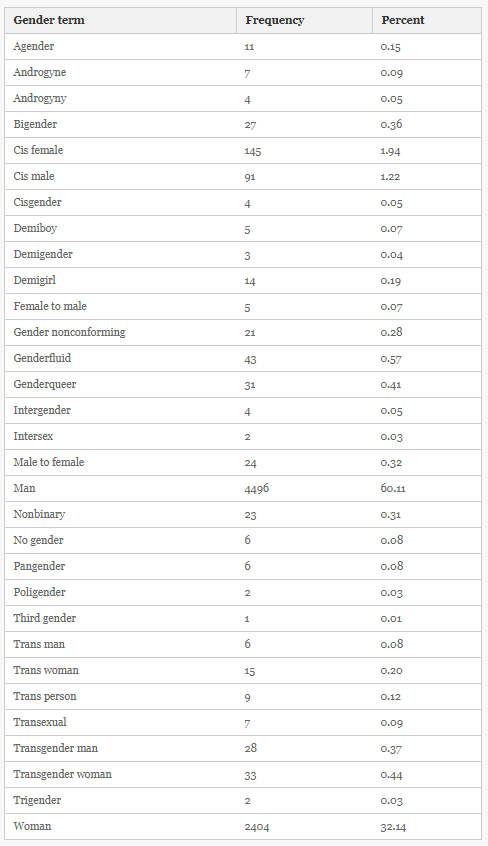

Frequency of participant by gender identification term

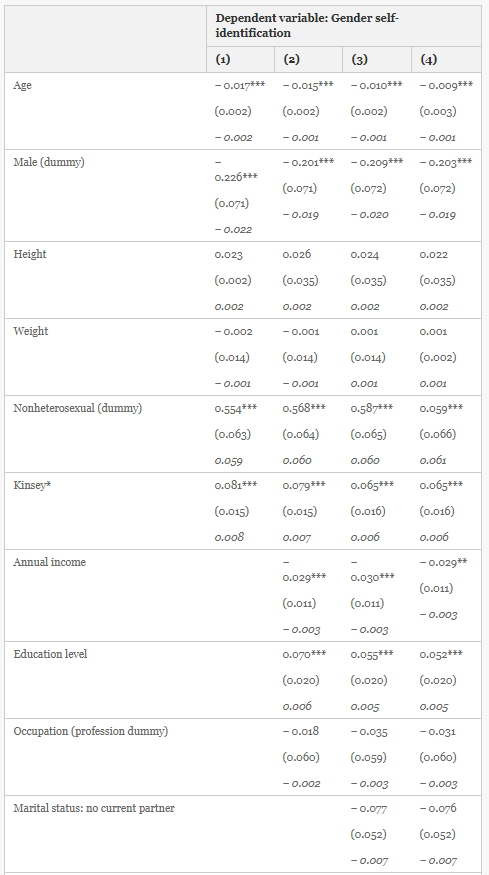

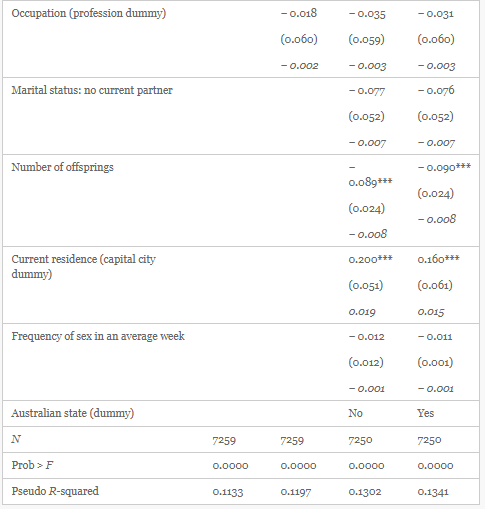

Factors related to nonbinary gender self-identification (probit model)

References

-

-

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Sex and gender diversity in the 2016 census, census of population and housing: Reflecting Australia—Stories from the census, 2016. Released 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017, from http://abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Sex%20and%20Gender%20Diversity%20in%20the%202016%20Census~90.

-

-

-

Blackless, M., Charuvastra, A., Derryck, A., Fausto-Sterling, A., Lauzanne, K., & Lee, E. (2000). How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis. American Journal of Human Biology, 12, 151–166.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2000). Gender differences in pay. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 75–99.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Buss, D. M. (1985). Human mate selection: Opposites are sometimes said to attract, but in fact we are likely to marry someone who is similar to us in almost every variable. American Scientist, 73, 47–51.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Carrera, M. V., DePalma, R., & Lameiras, M. (2012). Sex/gender identity: Moving beyond fixed and ‘natural’categories. Sexualities, 15, 995–1016.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Connell, R. (2012). Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social Science and Medicine, 74, 1675–1683.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1385–1401.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Davidson, S. (2016). Gender inequality: Nonbinary transgender people in the workplace. Cogent Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2016.1236511.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Deaux, K. (1984). From individual differences to social categories: Analysis of a decade’s research on gender. American Psychologist, 39, 105–116.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Factor, R. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (2008). A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3, 11–30.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Fleming, P. J., & Agnew-Brune, C. (2015). Current trends in the study of gender norms and health behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 72–77.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Harrison, J., Grant, J., & Herman, J. L. (2012). A gender not listed here: Genderqueers, gender rebels, and otherwise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBTQ Public Policy Journal at the Harvard Kennedy School, 2(1). Retrieved March 16, 2017, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zj46213.

-

-

-

Hoffman, R. M., Borders, L. D., & Hattie, J. A. (2000). Reconceptualizing femininity and masculinity: From gender roles to gender self-confidence. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 15, 475–503.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., & van Anders, S. M. (2018). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000307.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Jacobson, R., & Joel, D. (2018). An exploration of the relations between self-reported gender identity and sexual orientation in an online sample of cisgender individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1239-y.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Joel, D., Tarrasch, R., Berman, Z., Mukamel, M., & Ziv, E. (2014). Queering gender: Studying gender identity in “normative” individuals. Psychology & Sexuality, 5, 291–321.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Jones, T., Smith, E., Ward, R., Dixon, J., Hillier, L., & Mitchell, A. (2016). School experiences of transgender and gender diverse students in Australia. Sex Education, 16,156–171.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Kuper, L. E., Nussbaum, R., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Exploring the diversity of gender and sexual orientation identities in an online sample of transgender individuals. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 244–254.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Kuyper, L., & Wijsen, C. (2014). Gender identities and gender dysphoria in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 377–385.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Mallenbaum, C. (2016). Tinder update introduces 37 new gender identity options. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved March 16, 2017, from http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/life-and-relationships/tinder-update-has-introduced-new-gender-identity-options-20161116-gsr710.html.

-

-

-

McNeil, J., Bailey, L., Ellis, S., Morton, J., & Regan, M. (2012). Trans Mental Health Study 2012. Edinburgh: Scottish Transgender Alliance.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Mealey, L. (2000). Sex differences: Developmental and evolutionary strategies. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Morley, B., Pirkis, J., Naccarella, L., Kohn, F., Blashki, G., & Burgess, P. (2007). Improving access to and outcomes from mental health care in rural Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 15(5), 304–312.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

New York City Commission on Human Rights. (2016). Legal enforcement guidance on the discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression: Local Law No. 3 (2002); N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8–102(23) Retrieved March 16, 2017, from http://www1.nyc.gov/site/cchr/law/legal-guidances-gender-identity-expression.page.

-

-

-

Rankin, S., & Beemyn, G. (2012). Beyond a binary: The lives of gender-nonconforming youth. About Campus, 17(4), 2–10.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Richards, C., Bouman, W. P., Seal, L., Barker, M. J., Nieder, T. O., & T’Sjoen, G. (2016). Nonbinary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 95–102.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Richters, J., Altman, D., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M., de Visser, R. O., Grulich, A. E., … Simpson, J. M. (2014). Sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual experience: The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sexual Health, 11(5), 451–460.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Richters, J., Grulich, A. E., Visser, R. O., Smith, A., & Rissel, C. E. (2003). Sex in Australia: Sexual difficulties in a representative sample of adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 164–170.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Riggs, D. W., von Doussa, H., & Power, J. (2015). The family and romantic relationships of trans and gender diverse Australians: An exploratory survey. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(2), 243–255.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Rubin, G. (1975). The traffic in women. Notes on the “Political economy of sex”. In R. R. Reiter (Ed.), Toward an anthropology of women (pp. 157–210). New York: Monthly Review Press.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Rushbrook, D. (2002). Cities, queer space, and the cosmopolitan tourist. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 8(1), 183–206.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Schmitt, D. P. (2004). The big five related to risky sexual behavior across 10 world regions: Differential personality associations of sexual promiscuity and relationship infidelity. European Journal of Personality, 18(4), 301–319.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Smiler, A. P. (2004). Thirty years after the discovery of gender: Psychological concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles, 50(1–2), 15–26.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Stoller, R. J. (1968). Sex and gender: The development of masculinity and femininity(Vol. 1). New York: Science House.Google Scholar

-

-

-

Van Caenegem, E., Wierckx, K., Elaut, E., Buysse, A., Dewaele, A., Van Nieuwerburgh, F., … T’Sjoen, G. (2015). Prevalence of gender nonconformity in Flanders, Belgium. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(5), 1281–1287.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Weeden, J., & Kurzban, R. (2013). What predicts religiosity? A multinational analysis of reproductive and cooperative morals. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(6), 440–445.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Wellings, K., Collumbien, M., Slaymaker, E., Singh, S., Hodges, Z., Patel, D., et al. (2006). Sexual behavior in context: A global perspective. Lancet, 368(9548), 1706–1728.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Whyte, S., & Torgler, B. (2017). Preference versus choice in online dating. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(3), 150–156.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Whyte, S., Torgler, B., & Harrison, K. L. (2016). What women want in their sperm donor: A study of more than 1,000 women’s sperm donor selections. Economics & Human Biology, 23, 1–9.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Wilchins, R. A. (2004). Time for gender rights. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 10(2), 265–267.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

-

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 699–727.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

-

World Health Organization. (2016). Gender, women and health. “What do we mean by sex and gender?” Retrieved March 16, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/gender/whatisgender/en/

Statistical Resources

Descriptive Statistics (view full PDF)

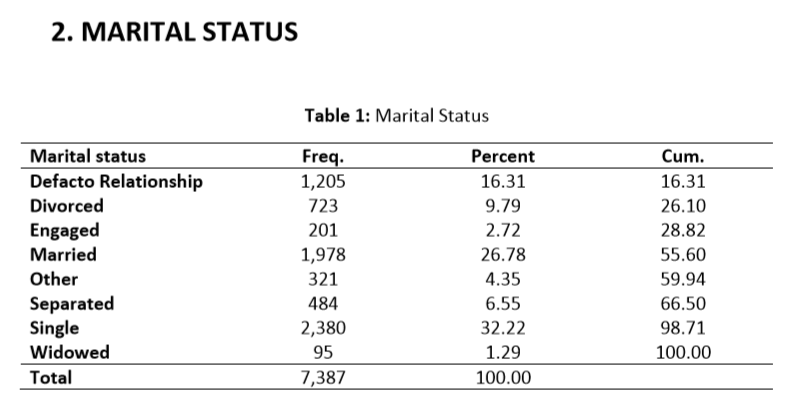

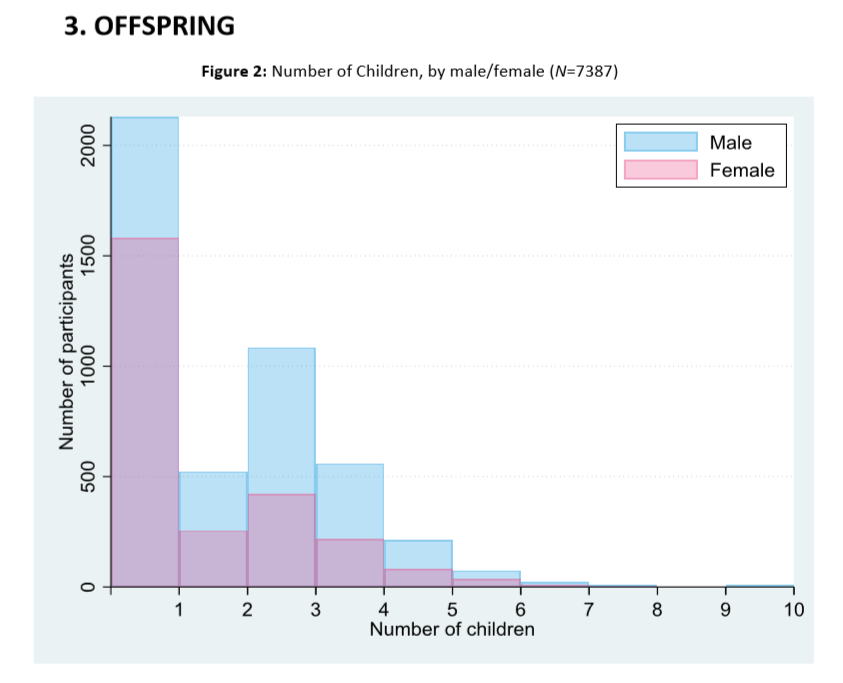

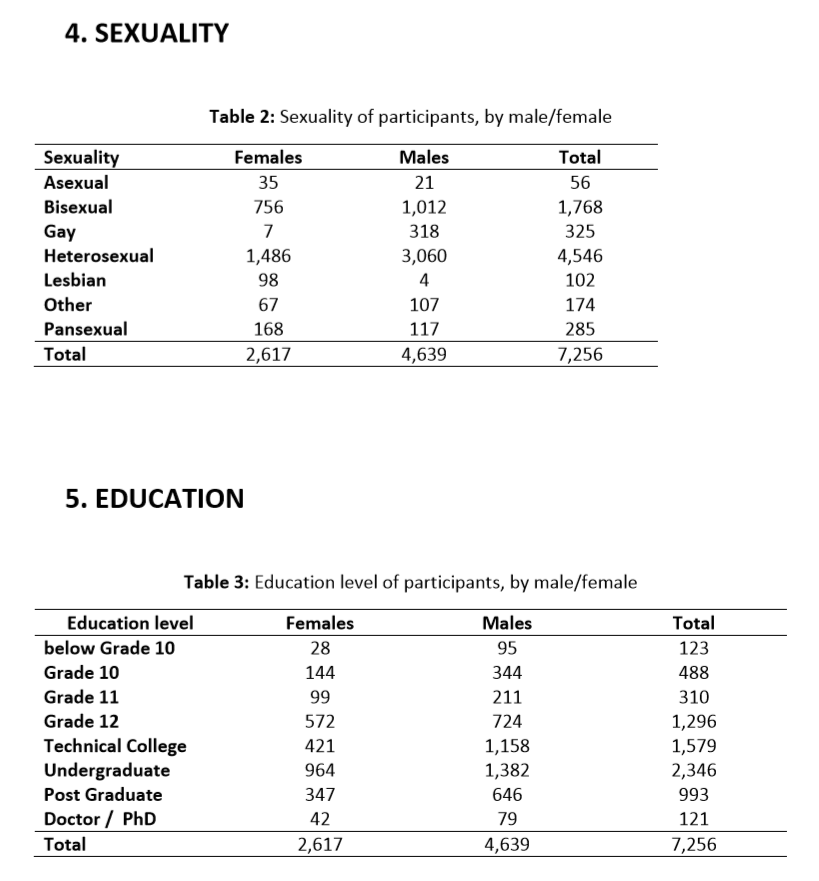

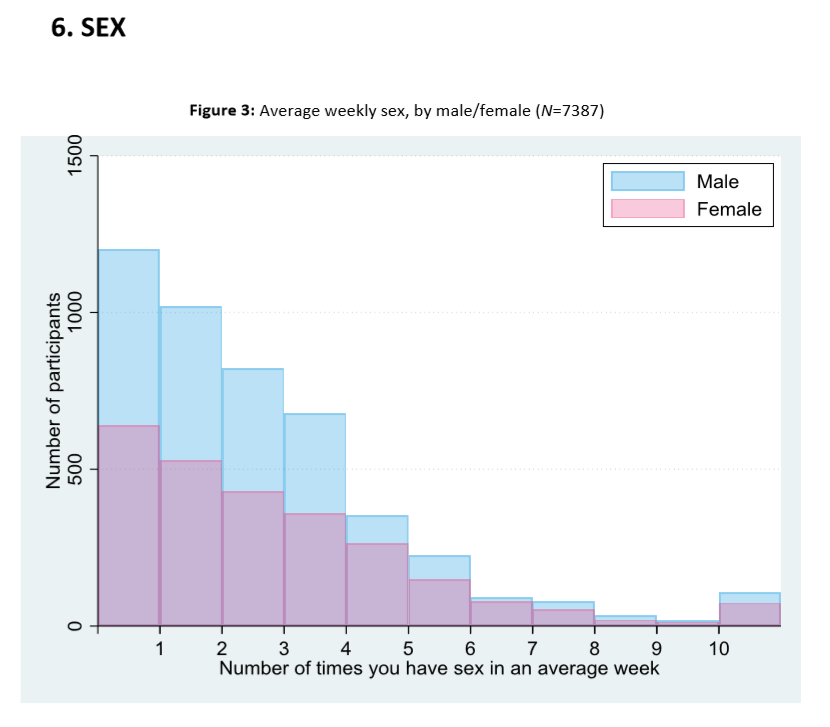

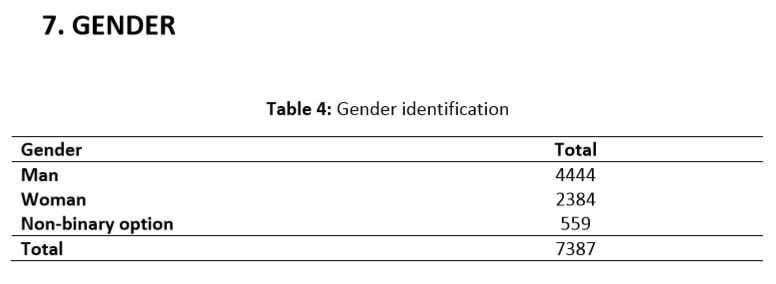

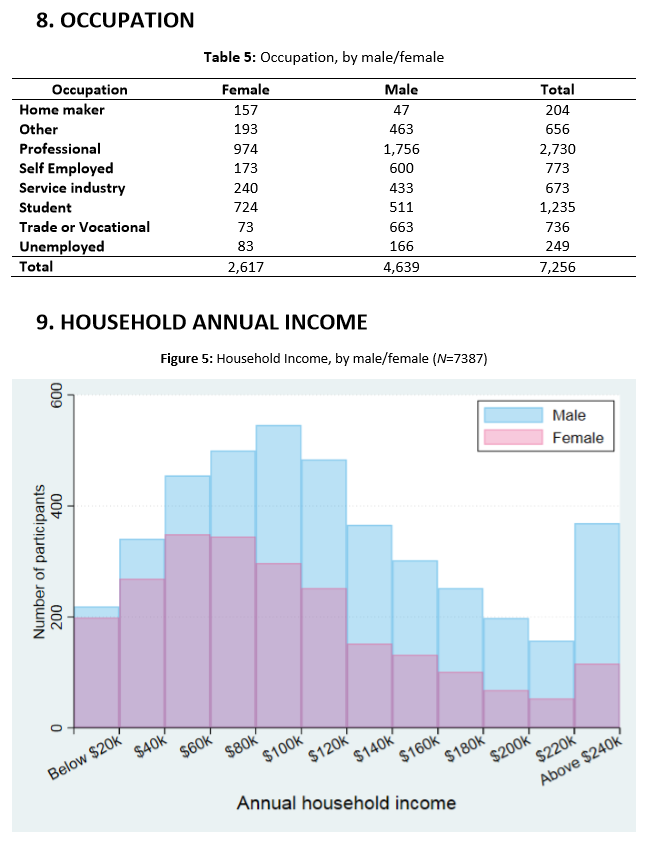

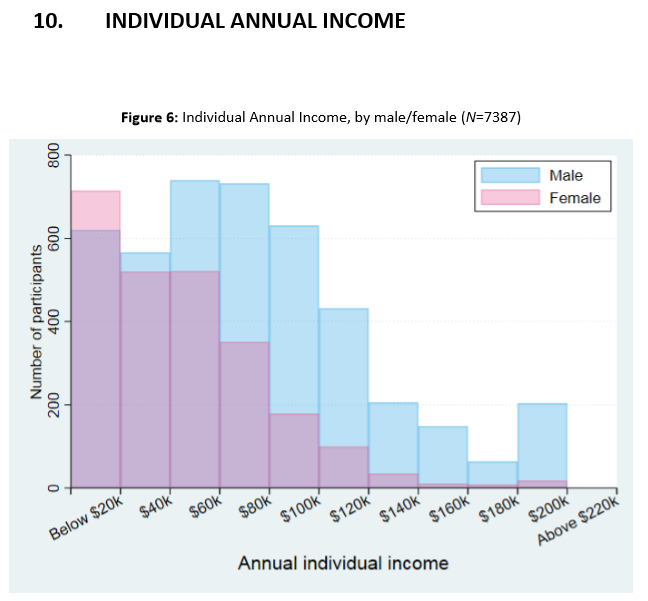

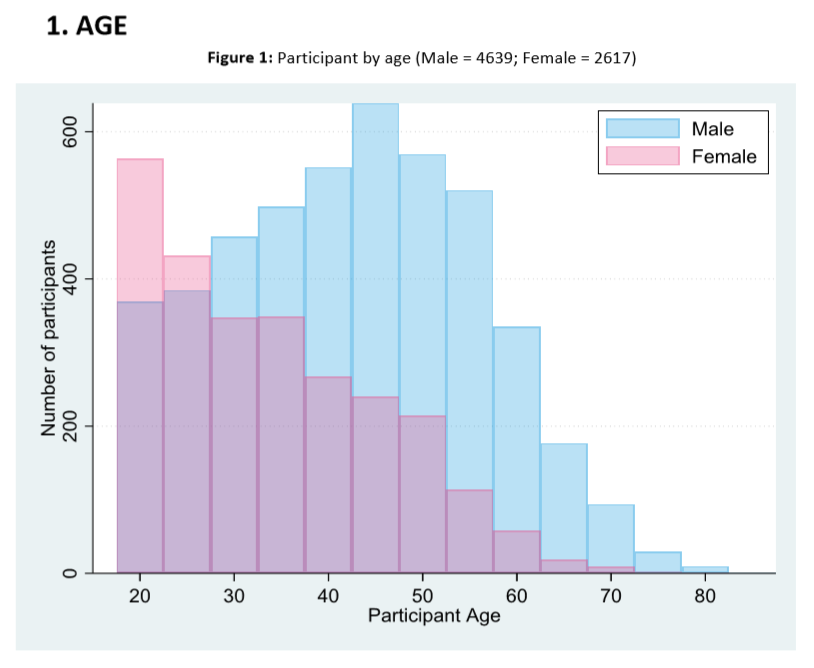

Presented here are some demographic summary statistics collected participants of the 1st Australian Sex Survey, conducted between July – September 2016.1

1 Please note, not all observations sum to total, as per the QUT Human Research Ethics approval, participants were not required to answer any question they did not wish to.